the making of the harris project

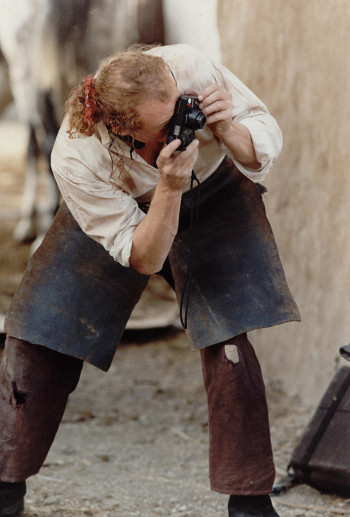

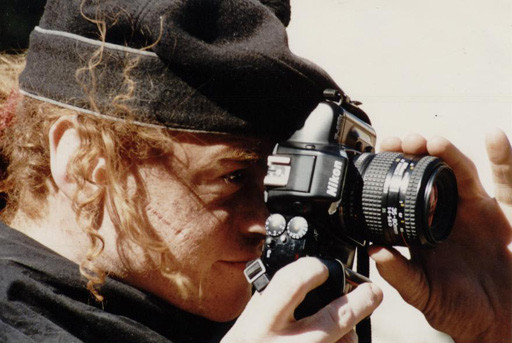

The Harris Project- an all encompassing term for all matters Harris- began with a desire to keep a photographic record of events on the first series of Sharpe.

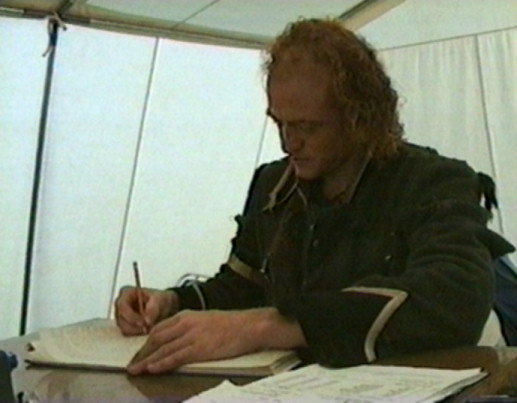

On that first shoot, I began a written diary that lasted all of one entry. The shock and awe of the incredible circumstances surrounding our first tour left me unable to maintain the discipline of writing daily entries in a diary.

This was something I bitterly regretted, as the McGann era Sharpe shoot was monumentally eventful and would have provided a very interesting read not just for Sharpe fans. I made up for this laxness by keeping a written diary for three of the remaining four years; years that provided many an interesting occurrence.

The Harris Project's first sustained documentation was a series of photos adorned with appropriate newspaper headlines and written comments that usually filled took two weighty tomes.

At some point during the first two years on Sharpe, I saw a handy cam video made by Mel Gibson on the set of 'Lethal Weapon 12' He walked about the set commenting on proceedings, introducing the crew and generally being quite funny.

It made entertaining viewing not only for fans of Mr Gibson. I quickly realised that his 'access all areas' to every aspect of the film making 'machine' combined with lively, witty presentation was the key to a successful video diary. With Mel's model firmly in my head, I took a video camera on set for the third series to record what had become for many people an awesome annual event.

I filmed everything that moved: actors, horses, caterers, drivers or street musicians, no subject was too trivial as I endeavoured to document what happens behind the scenes of Sharpe.

Originally, I had had lofty, unrequited ambitions to strike a deal with an ITV producer for use of my footage as part of one of the anticipated (by me) documentaries that would be made.

Ironically, the only documentary produced about Sharpe was made during the fourth series on our first trip to Turkey in 1995. The production company arrived on set the day I had chosen to cross the Black Sea to Yalta for a family visit. The result being the sole documentary made about Sharpe is minus one Chosen Man Harris.

Then along came the Sharpe's Appreciation Society and then the internet!

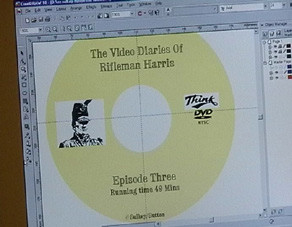

The SAS came into existence shortly after we finished filming the fourth series. It quickly became the focal point for a huge band of unconnected followers in the UK and eventually the world. By the turn of the century (20th into 21st), the venerable society was two thousand members strong; this is when I decided it was time test the waters by producing a pilot episode of my unique video diary.

Having no technical means to edit the video footage together professionally, I turned to my friend Drew Sutton, a digital image specialist. He transferred the footage, recorded with Hi-8 video, on to mini digital tape; then the exhaustive logging process began. Every minute was reviewed, so I could then make a decision as to which clips should be 'captured' by the computer.

For the first episode, I just selected the best bits in terms of entertainment and quality of visual image, stringing them together in chronological order. These bits were linked with graphics, music, photographs and fun edits all explained in voice over.

Episode 2 had a similar construction, though primarily, my philosophy and thoughts about Sharpe drove the film while still being chronologically faithful to the order of day-to-day events. The second episode flowed well enough but I still found it a little 'bitty'. To remedy this I commissioned another mate to write a score, plus other incidental music for the third episode.

The thrust of the third video diary had the death of Perkins as the motor for the narrative, a narrative punctuated with tangential details of relevant incidents and accompanying Sharpe history. I achieve these details with dips into the written diary for the daily minutia of goings on during a particular period, as well as photos from the albums. All of this layering hopefully gives it the seamless veneer of a proper documentary!

Once the clips have been 'captured' we trim them so they can be placed in a timeline on the computer, generally respecting the chronological order of the clips but other times not. After completing the basic time line, called a first rough cut, we transfer it onto a mini digital tape, then on to a VHS.

In the following period, we fine-tune all the connections between the clips in the studio, while at home I hone the narration to where I want it.

When I'm happy with the voice over script we record it onto the timeline.

There are times when the voice over is supplemented with a photo, known as a rostrum shot; the lens moves across a still image giving the impression of movement in the image. With the addition of rostrums, incidental music and graphics, the episode is considered finished.

With the completed film in the hands of the duplicator, I exhale a huge sigh of relief. It is particularly satisfying considering I began shooting the footage in 1994, with no guaranteed outlet for a finished product. It would have been a shame had the tapes not seen the light of day, but I was determined to make sure the project I dreamed up all those years ago came to fruition.

I owe a great debt of gratitude to all the film units featured in Harris over the years, especially for the blessing of members such as Sean and Daragh whose images fill my diary and make them special. And to our tolerant, exceedingly broadminded exec producers Malcolm Craddock and Muir Sutherland who have put no impediment in the way of producing the diaries.

However, what keeps the Harris Project a viable concern are you the Sharpe fans, the fans of Sean Bean and now fans of Harris. Your interest feeds my inspiration to continue the films and maintain their production as professionally as possible. So, long live Harris!

top of page ^

|